Mobilizing to Challenge Power for Safety and Equity in Nigeria

Interview with Nnimmo Bassey, Health of Mother Earth Foundation (HOMEF) Executive Director, Nigeria

In a riveting conversation, Nnimmo Bassey, a renowned activist, architect, poet, and pastor, delves into his transformative journey from spearheading Environmental Rights Action (ERA) to founding one of Grassroots International’s partners in Nigeria, the Health of Mother Earth Foundation (HOMEF). Bassey reflects on how historical struggles, his diverse roles, and the current political landscape shape his and HOMEF’s multifaceted approach to activism. This interview unpacks the dynamic strategies of HOMEF, the challenges facing West Africa, and the critical role of solidarity in advancing global justice. Bassey’s vision for HOMEF was driven by a desire for deeper focus and impact in environmental and social justice. Bassey discusses the influence of his upbringing and various professional roles, emphasizing how architecture, poetry, and pastoral work intertwine with his activism to foster holistic social and environmental change. He critiques the current political climate in Nigeria and West Africa, highlighting the reactionary nature of regional governments and the socio-environmental impacts of their policies. He points to both challenges and opportunities, noting the need for grassroots mobilization and political consciousness.

HOMEF’s initiatives and actions, including fossil politics, hunger politics, and the protection of community and culture, reflect a strategic shift towards addressing deeper systemic issues. Bassey outlines HOMEF’s efforts in combating fossil fuel exploitation, promoting agroecology, and combating genetic engineering, all while advocating for a just transition to sustainable practices.

The No REDD in Africa Network, a key focus for HOMEF, is re-emerging as a critical force against carbon trading and land grabs disguised as climate action. Bassey underscores the network’s role in educating and mobilizing grassroots resistance against the misleading promises of false climate solutions like REDD.

Bassey also emphasizes the power of global solidarity, arguing that effective environmental and social justice requires a united effort from workers, civil society, and communities. He envisions a collaborative approach to overcoming ecological and social challenges, highlighting the interconnectedness of justice and collective action.

This interview provides a compelling look into Bassey’s and HOMEF’s visionary work and the pressing issues of our time, calling for a reevaluation of current climate strategies and a renewed commitment to genuine, inclusive and people-led solutions.

Boaventura: Can you share with us about your journey and your transition from Environmental Rights Action (ERA) to the founding of HOMEF? What prompted this transition?

Nnimmo Bassey: I grew up in a time when liberation movements were very active in Africa. And so that influenced my knowledge and the kind of things that I paid attention to through my time in high school. And before then, while in primary school, my country had a civil war. So that also had an impact on my childhood. And then when I was in the university, I was indeed very active with literature from all kinds of struggles, from Frelimo, to ANC and SWAPO, all those groups that were circulating free literature across the continent. And then, of course, our country, Nigeria, was under military rule. So I became a part of the human rights movement the moment I stepped into my working life.

As a part of the human rights movement, we were campaigning against military dictatorship, and then looking for more humane relationships between power and the people. And I soon realized that the greater impact on the people was the abuse of their environmental rights.

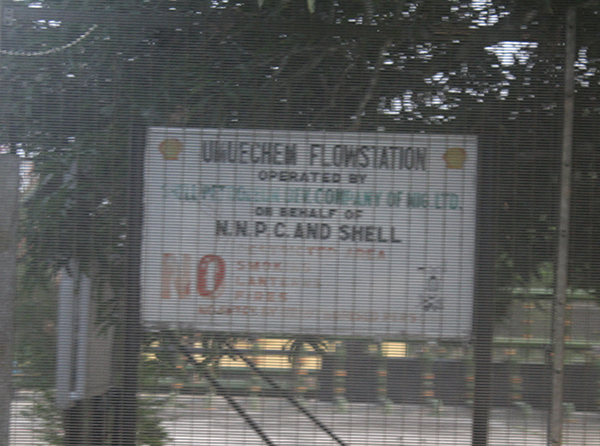

While I was in the human rights movement we started the environmental rights project. And the major area of focus, where there were most prominent abuses, again, with the military involved and the oil corporations, was the Niger Delta.

For more than two decades, I led Environmental Rights Action (ERA), first as a project under a human rights group and then as an independent organization.

It got to a point where, you know, when you’ve led an organization for so many years, you begin to think of what else to do and how. You begin to think about what could be changed? I decided at that time to start a new organization, the Health of Mother Earth Foundation, with the rights of Mother Earth or Nature as a central core. That meant basically narrowing down the focus of work.

In ERA, which is the Friends of the Earth International’s member group in Nigeria, the work is quite broad and required a big team to deliver on our mandate. I really enjoyed the networking at Friends of the Earth, and because we had so many members in the network from over 70 countries, the diversity was very, very enriching. But it gets to a point where you want to narrow down the work into a smaller, sharper focus. And this is what brought HOMEF into being, focusing on fossil politics, which covers issues of impunity, issues of neocolonialism, hunger politics, and asking the deep question about the root causes of these problems. And then knowledge, which is very central. I just felt, and this is what I’m still feeling today, that this is one space that needs a lot more work, the knowledge space. Because it’s what you know and how you interpret what you know that fashions what you do. If we don’t have the right understanding, and if we don’t analyze things from our own perspective, we don’t own the narrative – it becomes a bit more difficult to find the solutions. Recently, from last year, we included community and culture as a work focus which helps us to utilize cultural tools and impulses in our push for real solutions to climate justice, ecological justice and to holistically overturn the exploitative neocolonial system ravaging our peoples and territories.

Boaventura: You are most known as an activist, but I also know that you are a writer, an architect and also a pastor. How do you balance these diverse roles and how do they influence each other in your work and life?

That’s my kind of ministry, working with people who are disadvantaged and also helping to challenge people to think not just about what will happen after they’re dead, after they’ve died, but what is happening right now while we’re alive.

Nnimmo: Being an architect is very integrated with my being an environmentalist. Because even while studying architecture and in practice as an architect, I’ve always seen the design of spaces as a conscious way to build social cohesion and to give people access to spaces that enhance their dignity and comfort. I also find that architecture enables you to sometimes support people and society’s needs. Architecture can moderate behavior and get people to be calmer and not agitated or erratic, to want to share with one another, to be together, to build a collective in shared spaces. I’ve always had that social consciousness in design and, of course, always aim to be less wasteful in terms of materials use of energy by designing with nature in mind.

As a poet, I see architecture as poetry in concrete, in stone. The way you align the windows, the doors, the play with light, the overall spatial dispositions — their interpenetrations and movements echo our moving through ideas. The architect’s eye helps you to see the building, you penetrate the building, before it is constructed. So it helps your imagination, which is what we need also in activism.

Being a pastor is another way for me to express my humanity and also to realize that humans are not the only beings on the planet. It makes me see things very holistically and understand that we have a duty, a responsibility, to ensure that we don’t hurt other beings, the animals, the birds, the fish, the microorganisms in the soil. Living in harmony – harmony with oneself and with others. Understanding that we are here on Earth to support one another. And that it is only when we work in the collective that we get stronger. It’s also helped me in terms of building compassion for people who are suffering.

In fact, as a pastor, my main job has been relating with the unloved populations, the populations that are deprived, the populations that are sometimes ostracized from society. People who are discriminated against, people left on the roadsides of life, including the poor, the prisoners and the sick.

That’s my kind of ministry, working with people who are disadvantaged and also helping to challenge people to think not just about what will happen after they’re dead, after they’ve died, but what is happening right now while we’re alive.

So, everything is blended.

Boaventura: How would you describe the current political context in West Africa and in Nigeria in particular? What are the main challenges, and also opportunities, you and HOMEF see in the region?

Nnimmo: Nigeria has a very reactionary government at the moment. Over the past few governments, we’ve not really had anything close to having a radical, popular government. We have governments that are very right wing, governments that are totally at the apron strings of international financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank. We have governments that are extractivist and who churn out anti-people policies. Sometimes it’s just amazing that governments can go that way so fast and so far.

And so this has an impact on the way we organize and the kind of things that we’re pushing for.

Over the years, we’ve been campaigning against oil pollution and marginalization of oil field communities and expansion of sacrifice zones. Now we have a mass of people who are actively campaigning against that and defending their rights to a safe environment. And we’ve seen some positive responses. For example, the cleanup of Ogoni land based on the United Nations Environment Programme report of 2011. Now we’re campaigning to escalate that to a cleanup of the entire region, the entire Niger Delta. And now coalitions are coming together to make that happen.

Another area of major campaigning in Nigeria has been around food sovereignty and against genetic engineering. Now governments, being what they are, from their perspective, they always talk about food security. Over the years, we have campaigned that food security is okay, but food sovereignty is fundamental. You cannot have true food security if you don’t have food sovereignty. Because food security says, if you’re hungry, eat whatever is presented to you irrespective of whether it is appropriate or not.

And so that opens the way for genetic engineering, opens the way for industrial monoculture agriculture. Opens the way for importation of food rather than supporting local farmers, local economies and supporting the local ecosystems.

Now, this campaign has been going on for a while, but right now, Nigeria is really, really awake to the fact that GMOs are a big threat. And that we need to support local farmers. So we work with farmers, academics, women groups and youths to push for agroecology as a viable alternative that aligns with our sociocultural realities. We’ve seen farmers learn, share knowledge and capacities and replicate best practices.

We are seeing a new wave of strength. This is happening in the political system that doesn’t really care, that’s so reactionary, and does not care about the people or the planet. The people are arising to recover their dignity and work in their best interest.

Regional Politics in West Africa

Nnimmo: We’re also seeing what’s happening in Nigeria being replicated elsewhere in the region. But there are also some signs of hope. We have some hope, for example, in Senegal, following recent elections. The transition was not so smooth, but the election has come and gone and we now have a young person as president and hopefully there will be new and pro-people ideas going forward. The change that happened in Sénégal was quite unexpected because the prevailing system fought to prevent change from happening. That gives the hope that change can come at any time!

Now, also, we have the military, military governments in the Sahel — Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and even in Guinea. I am not a fan of military governments, so this is a kind of dire situation where it’s not very easy to predict where things are shifting. Military governments are not democratic, so you never can say what their main influences would be. You can notice rising tensions between the power blocs again. The Cold War is being played out in West Africa between Russia, China, and the US and Europe. This poses a number of challenges.

One positive thing is that the governments in the Sahel may be able to liberate themselves from the colonial influence of France, which has been very heavy in the Francophone areas.

But in a country like Ghana, which we were holding up as possibly heading in the direction of real liberation, we’re seeing a government that is totally colonial in nature, totally in the grip of international financial institutions and the powers behind them. Of course, all these governments are extractivist in nature. They have colonial extractivism as their focus. Senegal has just celebrated their first barrels of crude oil. And they are going for gas. It is a tragic replay of the false hopes that you can escape from the extractivist holes by digging deeper.

They’re finding the same thing in Ghana, which is in a very tough financial situation — the situation that comes with extractivism. When foreign exchange flows in from fossil fuel extraction, or from mining, etc., leaders tend to think that that is going to be a tap that will flow unimpeded and continuously. But the end result has been that these supposedly credit worthy nations get pulled into the debt trap. So indebtedness is a big problem for countries in West Africa. And that is impacting the pattern of policies and how things are being done generally.

I think the political future of West Africa is still on the balance. Right now, the best way forward is to build stronger grassroots organizations in all these countries.

First, for people to be able to build their own lives, irrespective of what the government is doing. And second, to be more politically conscious so that through organizing at the local levels, they can influence the way things are done around them.

Boaventura: Indeed, what is happening in the region is very interesting. The fact that there is this new rupture and something new is emerging. However, there is a need to watch what is happening. It’s not that it’s inherently progressive, although we see signs of, you know, overcoming neocolonialism. French neocolonialism. But how are we going to deal — or what kind of new relationship are we going to build — with the partners that Senegal, Burkina Faso and Mali are choosing? And how different will those relationships be from the past problematic neocolonial relationships, and so on and so forth? I think very interesting times are approaching in the region, and let’s see how it plays out.

HOMEF’s Campaigns

The thing that underpins everything we do is to build knowledge for liberation, to get people to frame and explain their situations and propose solutions. In Nigeria we work with coalitions that focus on socio-ecological transformation. Not just pure environmental activities, but going to the politics behind the negative things that we’re confronting.

Boaventura: Could you elaborate a bit more on some of the key programs and interventions that HOMEF is currently implementing in Nigeria and elsewhere?

Nnimmo: The thing that underpins everything we do is to build knowledge for liberation, to get people to frame and explain their situations and propose solutions. In Nigeria we work with coalitions that focus on socio-ecological transformation. Not just pure environmental activities, but going to the politics behind the negative things that we’re confronting. And this led us to begin the Niger-Delta Alternatives Convergence and the production of a manifesto for socio-ecological transformation of the region. This year, we took that up to the national level and had the national convergence that produced a national charter for ecological transformation.

The aim is to make the manifesto and the charter very strong advocacy tools for both political leaders and community leaders. An interesting thing is that the convergence has managed to bring together political actors, traditional cultural actors, women, youth, and people from the civil society space. It’s truly all-encompassing because we realize that we cannot really push much in the direction of having a safe, clean environment, as enshrined in the African Charter for People and Human Rights, unless all the sectors understand that without a safe environment, you cannot enjoy the right to life.

When people say Africa has a young population, my question is always what happened to the old population? Why is it that we have so many youth and fewer elders? It’s not because we are breeding like rabbits. It’s simply because people are dying early. Nigerian life expectancy is 56 years for women and 53 for men. In the deadly oil fields of the Niger Delta life expectancy is an abysmal 41 years. If that’s the average life expectancy, it shows that there is something fundamentally wrong. Pollution and other manifestations of environmental harms are killing our people. Our fight is a fight for our very lives!

And this is why environmental rights and the rights of Mother Earth and environmental activism are critical. If we rescue our environment, people are going to live longer, better and in dignity. There will be no « Africa has a young population. » It’s actually an insult right now to make us blame ourselves rather than looking at who has created the problem. We cannot really popularize this kind of counter narrative unless we bring all sectors together to holistically look at what the challenges are.

Fossil Politics

In our fossil politics campaign, which is also a climate change campaign, we are looking at just transition, with an emphasis on the justice in that transition. A just transition that is people-centered and community-centered — not one that is drawn up at the center, but one that comes from below. We’re also working against the reckless divestment moves by international oil companies. After close to 70 years of reckless pollution and exploitation, they are now trying to sell off their assets. As they move into deep waters, the deeper the water, the less they pay to the government. Because almost all the money will go, according to them, into production. And they are the ones determining what the cost of production is. It is a wicked con game. So we’re saying, if you want to divest, fine. We want you to get out of our territory. But you have to clean up the mess. Clean up and pay for the damage done. It’s the ecological debt we are demanding.

We’ve always been campaigning against oil theft. Oil theft is growing in Nigeria at an industrial scale. It’s so annoying and so insulting. We always campaign that one of the reasons why this has gone on is that Nigeria has never known exactly how much oil is being extracted. Because the oil fields are not properly metered. And just recently, the government said they’re going to install meters. We’ve been campaigning for this for years. Now they want to install meters. Good. Better late than never.

Well, now the oil wells are drying up. Nigeria is not able to produce. They produce about 1.2 to 1.6 million barrels a day — previously they were producing up to 2 million barrels a day. They’re pretending that it’s because of violence and conflict, but it’s not true. The wells are simply drying up. So we’re pushing for that quick transition from dependence on fossil fuels to an environmentally safe way of production and consumption.

We want you to get out of our territory. But you have to clean up the mess. Clean up and pay for the damage done. It’s the ecological debt we are demanding.

We continue to work with communities to build resistance. I’m speaking to you from Port Harcourt, where we’re going to do a workshop to strengthen the resistance to reckless exploitation of not just the environment, but of the minds of our people. We have to get more people conscious of what is going on. We are also having a School of Ecology on ending sacrifice zones. We’re aiming to build partnerships with universities to have these kinds of knowledge sharing which fits into the Global South Eco-Social Manifesto, which demands an end to the expansion of sacrifice zones. Sacrifice zones are expanding everywhere you look. West Africa, East Africa, South Africa, everywhere. They’re looking for more oil, more so-called critical minerals. They don’t respect protected areas or World Heritage areas. Anywhere is fair game for extraction. Whether it’s in Senegal or Uganda or Namibia, nobody cares which area should be protected. We’re losing our forests, mangrove forests. And there’s an assault on the deltas. I think that should be a good project – halting the assault on the deltas.

So we can combine what’s going on in Senegal, Nigeria, Namibia and other places that have really come together, fighting from different directions on the same strategy.

Hunger Politics

On hunger politics, our campaign is on promoting agroecology, and we’re seeing a lot of success on this. One community offered us land for use as a demonstration farm. We’re actually thinking of helping the communities to own that demonstration farm and do collective work through agroecological means.

We are taking that around the country and also working with the African Food Sovereignty Alliance’s My Food is African campaign. And then the campaign against genetic engineering. Nigeria has been the epicenter more or less in West Africa because when Nigeria is contaminated, our neighbours Cameroon, Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso and Benin Republic are at risk. In the coming weeks, we’re having a national conference on genetic engineering to build more understanding.

We also have training for the judiciary, for lawyers and judges. The first time we went to court, the court didn’t really pay much attention. This has necessitated our sharing of knowledge on the subject. We’re also organizing the farmers and the fisherfolks of the Fishnet Alliance to resist genetic engineering.

Community and Culture

Under community and culture, we’re looking at utilizing cultural tools, music, poetry as key Justice tools. And we’re also thinking of how to have a school of social comedy that will take on environmental issues and make people laugh while learning. There has to be joy in the struggle!

In Ikike, which is our knowledge base, we have the School of Ecology. We’re taking all the main focus areas of our work and finding ways to spread knowledge. Everything we do is still embedded in the community, although we also have a focus at the national level.

In the coming weeks, we will be leading a retreat for our senators on climate change. That’s at their own request. So we’re going to do that with some partners and help them to understand what climate justice means because the government doesn’t say anything about climate justice. All they talk about is Net Zero and all the same things that we hear about at the United Nations’ Conference of Parties.

The Politics of the Conference of the Parties (COP) on Climate Change

All these are very colonial ideas of expanding the sacrifice zones in the Global South. Even the energy transition, which doesn’t really look at the injustices in the extraction of the so-called critical minerals, is also a big problem. And then the purchase or acquisition of huge chunks of African land for “blue carbon,” or whatever kind of carbon, for carbon offsetting is a threat to our communities, a threat to our political and environmental sovereignty.

Boaventura: I know HOMEF has been a consistent participant in the UN Conference of Parties (COPs), even as progressive social movements have criticized these conferences, and some have ceased participating in them. Could you elaborate on HOMEF’s engagement with the COPs and the positions it advocates for at these summits? What are the major topics, trends, and actors within the COP? Please help us understand the future of this space, especially with the significant momentum expected next year in Brazil, where there is considerable mobilization to host a parallel event. What is HOMEF’s position on the UN Climate Summit, and how does HOMEF view the broader COP space?

Nnimmo: The COP is a very contradictory space. It’s supposed to be a space for forging real climate action. But every year we’re seeing a slide backwards. The COP has been totally co-opted by polluters. And now from the Paris agreement, our position is that since the COP became a a space for voluntary action, with a focus on nationally determined contributions, there’s no way to really enforce what needs to be done. So, as long as it remains a voluntary space, the world is just getting together to feel good.

Our engagement with the COP is mostly with the outside space because the conference provides a space for social groups, activists, and for civil society organizations to come together and really strategize and organize.

So in terms of the benefits of having the COP, I think the outside space is the benefit. Over the years there’s been a shrinking of the space for protest. It’s almost like they just allow people a few 30-minute slots to perform, like performances, not really a real process — something to just keep the activists busy. And then the day of global protest is now restricted to the venue of the COP. So it doesn’t have the means of interacting with people who are outside of the COP venue. I think that’s a big mistake, a big loss, a big retrogression that we’re seeing with the entire exercise.

Over the years, the trend of the COP moving towards market environmentalism and false solutions has become very clear. Right from Kyoto, in 1997, there was a push for inclusion of market mechanisms as climate action by countries like the US and others in the global North.

But the market that created the climate crisis cannot solve the crisis. And now there’s been debates since the Paris Agreement on Article 6 of the Agreement, with the tendency to try to bring in all the false solutions like geoengineering, more carbon offsetting, “nature-based” solutions, etc. All these are very colonial ideas of expanding the sacrifice zones in the Global South. Even the energy transition, which doesn’t really look at the injustices in the extraction of the so-called critical minerals, is also a big problem. And then the purchase or acquisition of huge chunks of African land for “blue carbon,” or whatever kind of carbon, for carbon offsetting is a threat to our communities, a threat to our political and environmental sovereignty.

And this is being projected as a means of fighting global warming. Just look at the colonial nature of carbon offsetting. A country buys up a forest (I’m using the word “buy”) or leases a forest in Africa, and “protects” (owns) the carbon in the forest. And the country where the carbon/forest is located cannot claim the carbon sink as their own climate action. It’s whoever paid for the carbon — maybe a country in Europe or North America, or perhaps Japan or Australia. If they bought the forest in Africa, that country will count that forest, the carbon in that forest, as their own part of their nationally determined contribution, as part of their climate action.

We find this very, very colonial. Now you’ve extracted the carbon, you are keeping the people off their resources, and you are claiming that you’re doing the right thing. The COP has offered very big open spaces for these kinds of colonial relationships.

And this is why the space outside the COP is also a space to pressure the negotiators to realize that we have to decolonize the COP itself. And when they talk about loss and damage, we’ll always be saying that the COP itself is lost and damaged.

So, you have to rescue the COP from voluntary climate action to binding measurable climate action, as was highlighted and as was the case in the first Kyoto Protocol.

No REDD in Africa Network

Boaventura: The No REDD in Africa Network, which HOMEF is part of along with other organizations and movements in Africa, is being relaunched. Could you provide an update on what is happening within the network? What strategies are being implemented, and what are the future plans for the network?

Nnimmo: Unfortunately, the network wasn’t very active. We started at the World Social Forum in Tunisia (2015). And now the re-emergence of the network couldn’t have come at a better time. Now is the time that countries are losing sovereignty over their territories because of REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) projects. And people don’t realize the implications because they’re looking at carbon credits and how much money may come to the country.

But this is a new form of slavery that the No REDD in Africa Network will very openly and vigorously combat. We are at a time where territories are being grabbed in Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Liberia, Nigeria, all these places, so the No REDD in Africa Network couldn’t have come at a better time. The strategy is to do an analysis of what the situation is. And from there, to draw up action plans that would be taken to expand the grassroots understanding of the falsehood in the whole REDD+ construct. Then to build resistance to it, and to cause the political leaders to not just see the trickle, the few coins that drop into their coffers, but to see the holistic bigger picture, and the loss that will happen to our countries.

The No REDD in Africa Network is a tool and a platform. We’re seeing it as a network that will really wake people up to why we need real climate action.

The power of Solidarity

Boaventura: How do you view the power of solidarity among working people around the world? How important is this in advancing social justice, climate justice, environmental justice, and so forth?

Nnimmo: Very important indeed. And let me just say that the ecological crisis cannot be solved without the deep involvement of workers. And workers cannot fight for their own best interests, except if they see themselves as part of communities. And so it’s two-way traffic. Civil society has to work to bridge this gap, to see the exploitation of labor as something that has to be confronted; to see the right to safe and decent work and livable wages as critical; and at the same time help workers to be embedded in civil society in a much more organic way that we see in some countries right now.

For the overall impression of our environment, for justice to reign, for ecological justice, for food sovereignty, and all that, workers and other actors have to enjoy a level of cohesion and collaboration where these bridges of solidarity must come from understanding that we cannot do it separately. We have to do it together. The power of labor is so great, especially when extended to struggles beyond the question of wages. Wages are important, but we also need to be alive to enjoy the wages that we’re earning. And so solidarity means common understanding — it means cohesion, it means love, it means joy, it means laughter, it means celebrations together. And this is what we have to build. Solidarity helps us to build sane, safe, equitable and productive societies.