Is the Solution to Climate Change Caring More About People?

Grassroots International is proud to be a member of the CLIMA Fund – a pathway for funders to directly support Indigenous, women and youth-led work building climate resilience and mitigating climate chaos.

The SF climate summits exposed the deep rifts at play in the struggle to tackle climate change. How do we think about justice for Indigenous peoples whose resources have been extracted for corporate profit throughout modern history while attaining commitments from Global North economies to reduce their emissions and harmful practices? How do we leverage multilateral funding while supporting power-building at the local level? Most of all, how do we embrace a multiplicity of strategies for climate action – because we desperately need to take action – while protecting communities, especially those most affected?

Solidarity to Solutions was a week of uplifting grassroots climate leadership to counter the narrative of the Global Climate Action Summit that corporations and national leaders will move us towards a climate safe, equitable future. Here are some of our reflections, as funders, on navigating those spaces.

The Profound Disconnect – Lindley

An audience member asks: “There are hundreds of millions in these multilateral financing mechanisms. How do you ensure it reaches the people that are directly impacted by climate change – the grassroots?” The speakers double down on their assertions: “These mechanisms were set up to fund governments that have contributed least to the problem – and funding those governments will trickle down to communities.”

Yet resources rarely ‘trickle down’. We know this as funders whose organizations have spent decades building trusted relationships with grassroots movements across the globe fighting the fossil fuel economy and building regenerative economies and food systems. We know these movements are starved of the funding international agreements have promised them.

This was one among hundreds of moments when I saw different advocates – all sincerely campaigning for what they believe are solutions to deteriorating land and life – miss each other. Why weren’t there global leaders and funders at the summit highlighting grassroots solutions? Why did Indigenous Peoples have to fly from across the globe to U.S. press rooms to advocate for their local streams to stay drinkable? Why were hundreds of millions pledged to technologies that have yet to be tested, while local communities are starved of funding to support millenia-old strategies that sequester carbon and support their resilience and sovereignty? I couldn’t help but think that we miss each other not for lack of need, but for lack of listening.

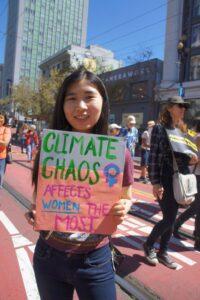

The Disconnect Continues: the Fight for Recognition of Women and Indigenous lives – Olivia

I found it remarkable the number of times I heard the phrase “women are positioning themselves to be the ‘new protagonists’ on the climate justice scene.” Remarkable because it feels so out of touch with the reality that women have been leading this work for decades. They have had to because how we treat women is how we treat the environment. This isn’t a cause women are casually taking up. Our world and all of our lives depend on it.

At the Women’s Assembly for Climate Justice organized by WECAN International I heard testimony after testimony of the correlation and compounding effects of miscarriages, environmental pollution, and oil spills, and thus of cancer and oil refineries on Indigenous territories. So much cancer that to be a young Indigenous woman or woman of color living in low-income geographies is to know cancer intimately. I repeatedly heard about the continual murder and disappearance of Indigenous women, and how this horrific trend is always mentioned as “just a trend.” A data point — something on the periphery, not a moral injustice or genocide. And even if it is spoken about with such gravitas, it is seen as a social justice issue separate from climate and not of the same urgency as global warming.

But these points are not separate. The power structures that extract from the environment are also to blame for the stark inequalities in the day to day lives and safety of men and women, particularly women of color and Indigenous women. Referencing climate justice, Eriel Deranger, Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation and Executive Director of Indigenous Climate Action said, “It’s about the land and the sky, but it’s also about the people that are dying. Until those people are the ‘right’ people no one will care.” Women and Indigenous lives are not equitably valued, even amongst “environmentalists.” Which means we must open up our own implicit bias to scrutiny and we must do better to fight for lives alongside land.

Women are speaking not for the first time, but perhaps for the first time this loudly. And it’s to everyone’s benefit that we do not stop.

The Disconnect in Decision Making and Indigenous Participation – Allison

I spent time throughout the Global Climate Action Summit with an indigenous youth climate activist named Ivan Torafing. Ivan is an activist from Baguio City, Philippines, who in addition to his many responsibilities, helps make grants through our fund (Global Greengrants Fund) to youth climate activists across Southeast Asia. He observed early on that youth were not well represented at GCAS, and certainly not Indigenous youth. Indeed, Indigenous groups, despite being sovereign “subnational governments” in their own right, were often ignored and left out of the conversation, as demonstrated by street protests across San Francisco led by Indigenous peoples who were demanding entry into the conference. (The U.S. politicians were occasionally so tone deaf that they thought the protesters were “San Francisco environmentalists protesting an environmental conference”). What does it feel like to be both indigenous and in your twenties, knowing your generation will suffer the impacts of climate change altering your air, land and water, more than any earlier generation who caused it, and yet still see youth and indigenous communities excluded from conversations where decisions are being made about their future?

But throughout, Ivan was unphased in his outlook. He knows that youth networks like the Asia Pacific Indigenous Youth Network are expanding their efforts and advancing their solutions for protecting the environment in the midst of a rapidly changing climate. He knows that real solutions are not coming from the large monied, boardroom conversations about those very forests where his family is from. In fact, he puts his attention instead on the everyday citizens stepping up, as indigenous groups are doing around the world.

At the end of the conference, Ivan returned home just as a cyclone hit and devastated his country, the very epicenter on his hometown. He spent two nights in the Manila airport before the road was cleared enough for him to go home and help his family. The “super typhoon” was the second to hit the Philippines in five years. I spoke to Ivan a week later. Again, he was still unphased. This is the reality of the world he lives in today. He says he cultivates calmness, for he knows that the absurd environmental calamities around him could destroy his spirit. Instead he channels his anger into productive work. Ivan and countless others deserve public platforms and decision making spaces in which their perspectives are fully considered.

Indigenous Peoples make up about 5% of the world’s population, but 80% of the biodiversity on Earth lies within Indigenous lands. This is not coincidental. Indigenous people, and particularly Indigenous women, are reminding the rest of us what is at stake. Yet GCAS seemed to show us a very different picture – one in which frontline voices continue to be marginalized and funding does not reach those returning home to climate-amplified disasters. What we’ve heard from the youth, women, and Indigenous groups that we fund is that they want fewer assumptions, and more allyship. Less teaching and big ideas, and more listening and trust.

If we support the self-determination of impacted communities, solutions trickle up. If Indigenous women are protected, we all are. If Ivan is safer, we all are.