We are in the Movements, But Lack Visibility

Guatemalan Sandra Morán, although well-known within social movements and articulations — especially feminist — in Latin America, gained prominence in the alternative media because she became, in 2015, the first lesbian representative of the Congress of the Republic of Guatemala.

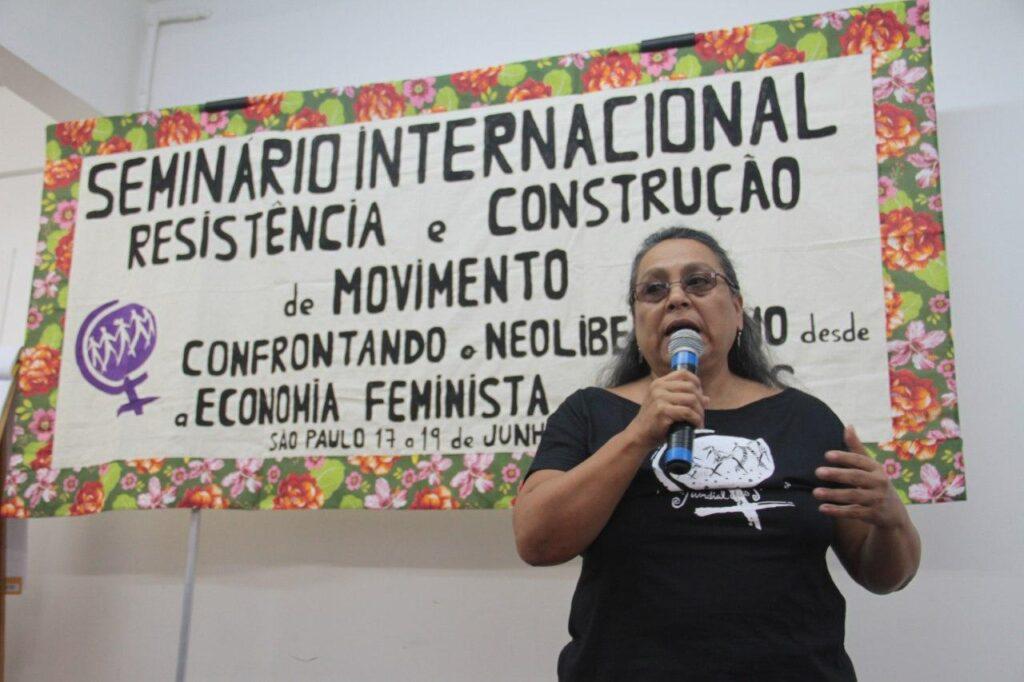

Passing through Brazil, where she participated in the seminar “Resistance and Movement Building: Confronting Neoliberalism from Feminist and Common Economies,” organized by the World March of Women (WMW), a movement that she is a part of, Morán spoke with Brasil de Fato on her participation, Guatemala’s presidential elections, which took place last Sunday (16), the current moment of feminism and lesbian visibility.

Trajectory

Morán is 56 years old and has a long history in social movements. Her political activity began at the age of 14 in the student movement. Since then, her struggle has gained multiple perspectives, so that today she could act from these multiple places and positions.

“I have been developing my participation in movements from the various identities that I have. I joined the grassroots movement from the student movement when I was still in primary school, at age 14. Then I went to the university student movement, the Revolution, then I went to music and went to the feminist movement, all this is part of my own journey as a person and an activist of the social and revolutionary struggle,” explains Sandra.

With a degree in economics, Sandra dedicated her early life to the underground youth movement. Between 1960, the year of her birth, and 1996, Guatemala experienced an intense Civil War. In this context, at age 21, she went into exile, living in Mexico, Nicaragua and Canada, where she was part of the solidarity movements.

She only returned to her country in the last years of the armed conflict and was an active part, as a member of Sector de Mujeres (a Grassroots International partner), in the campaign for the Peace Agreement, signed by the government of Álvaro Arzú and the guerrilla unit Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca.

For her, these elements culminated in her political activity as part of the World March of Women and as a Deputy from 2015.

“Every moment of life becomes a synthesis of the accumulation that the political moments occur throughout your life. I moved from the feminist movement and this movement gave me the opportunity to synthesize the feminist struggle, the rights of lesbian women, the LGBT community and today, as a Deputy, this helps me a lot because I have been working on the theme of sexual diversity, with women, with youth, with people with special needs, that is, I have, due to my personal experiences, I’ve had this possibility of knowledge and struggle,” says Morán.

Parliamentary activity

In the 2015 elections, Sandra Morán was elected MP for the left-wing Convergence party and began to connect her struggle from the social movements with her parliamentary performance, alongside Álvaro Velasquez, a researcher (who died during his term in 2017), and Leocadio Juracán, peasant leader.

Although she was elected as representative of the social sectors and the feminist movement, her entry into the institutional world did not happen without conflict, as she comments:

“Between me and Leocadio, for example, there was a difference. He entered as a strategy of his organization with the political party. And all the work he developed and we developed together was part of strengthening this peasant strategy. So his mandate became a new tool of a popular and peasant strategy. In my case no, it was not the strategy of the movement and even when I entered the mandate, my alliance separated from me with the understanding that there can be no connection between the political and the social. In my point of view, this is a misconception. I’m closer to the way Leocadio works.”

The onus that led to her entry into the Central American country’s parliament led her to look for other ways to honor the 32,000 votes she received.

“I have been able to create political participation groups, specific spaces to discuss and to create strategies. So I believe that it should be part of the political discussion of the movements that comrades and companions are in these spaces, as part of a strategy. We would say: three inside, thousands outside. Because what we did was amplify the voice of the outside. Because being in Congress is having power, just as being in the street is having power, but they are different forms. In Congress, decisions are made that affect the life of the population,” she recalls.

One of the bills promoted by Morán is the Girls’ Protection initiative, a result of a collective elaboration of the country’s feminist movement, which seeks to establish a series of protection measures and public policies aimed at the female population under the age of 14. One such measure is the authorization of voluntary termination of pregnancy for girls who are victims of sexual violence, sexual exploitation or trafficking.

As of May of this year, 1,963 cases of pregnancies of 10 to 14 year-old girls in the country were reported, according to data from the Reproductive Health Observatory. This fact becomes even more concerning when considering the factor of sexual violence. In the first quarter of 2019, 567 cases of sexual violence against girls aged 10 to 14 years were reported.

However, the bill that seeks to solve this serious social problem is not only considered secondary by most of the congressmen, but was also treated as a threat to the country and used by the conservative right to campaign against the “gender ideology.”

Sandra comments that because she is the proponent of the project, she has become one of the main targets of the fundamentalist sectors in Congress.

She also says that the issue of abortion, projected in the feminist struggles in South America, especially in Argentina, is an even more difficult issue in the Central American country.

“In Guatemala [abortion] is a taboo subject. I introduced a law that was not about abortion, but had one article about it, and I’m known as an abortionist. We do not even fill a block with people to defend this theme. It is an important theme, but it has always been taboo in Latin America,” she says.

Rise of Feminism

The popular leader closely follows the recent struggles of feminism in Latin America and in other continents as a former member of the International Committee of the WMW. She, who began her politicization the 1990s, when the women of the continent began to articulate to resist against the growing neoliberalism in the region, analyzes the factors of the mass feminist mobilizations in the recent times.

One of the elements pointed out by Morán is the protagonism of the youth that, for her, “have an important vital energy” to propose new forms of organization. The other, which she sees with concern, is what she calls “unstructured masses”:

“That means that today you can participate in a march, but not be part of any organization in an organic way. In Guatemala we had an experience like this in 2015, when there were big demonstrations that started with 25,000 and ended with 150,000, but after all this wide mobilization we only have small groups organized today,” she says.

For her, among the main challenges for the popular and anti-capitalist feminist organization are articulating massive mobilizations but maintaining a continuous organizational structure and facing the commodification of feminist symbols.

“Capitalism has always had the ability to make a commodity any icon, such as Che Guevara, for example, treated as an icon without content. Also, Frida [Kahlo] is an icon now that suddenly is everywhere, in fashion, in shoes, in bags. And it is an icon that we can claim, but it is now an icon of popular culture, which can be commodified. This has always existed and is a challenge for us,” she concludes.

Elections

Amidst the rise and popularization of feminism, Guatemala’s presidential elections last Sunday, June 19, gained a foothold in the international scene as it was an electoral dispute with initially four female pre-candidates. Among the four women presidential candidates, only two, Sandra Torres, a Social Democratic candidate and former first lady of the country, and Thelma Cabrera, an Indigenous and peasant candidate, competed in the first round.

Morán emphasizes the participation of Thelma Cabrera, who despite being in fourth place in the dispute, raised important issues during debates, such as the proposal of a Plurinational State, with autonomy for Indigenous peoples.

“Obviously, only one candidacy is a result of the popular struggle, which is that of Thelma Cabrera, who was in fourth place. There were fifteen candidates and she was in fourth place: woman, peasant, Indigenous. She came in fourth place with the urban population vote, in what was called a “rebel vote.” In addition, she is calling into question a new Constitution for the country, based on another model of well-being, so that’s important,” she says.

The other two pre-candidates, Thelma Aldana, former Republican prosecutor who has become one of the most recognized figures in the political scene for leading important investigations on corruption along with the International Commission Against Impunity (CICIG), and Zury Ríos , a MP for 16 years and daughter of former dictator Efraín Ríos Montt, had their candidacies suspended by the electoral courts for very different reasons.

Ríos could not run because of a decision by the country’s Supreme Court based on an interpretation of an article of the Constitution that prohibits participants from a coup to run for president, as well as impeding the postulation of their descendants for office. Aldana, meanwhile, had her candidacy blocked on charges of public money-laundering and tax fraud, allegations she and a number of sectors considered a case of prosecution for investigating the country’s current president, Jimmy Morales. For Morán, Aldana’s charges were a way to get her out of the election because she was first in polls.

“The other three, including the daughter of Efraín Rios Montt, are long-time politicians. [Ríos] was a deputy and a well-prepared, right-wing person who wanted to run. There was Thelma Aldana, a former prosecutor, who if she stayed, would be in the second round today, so they did not let her be a candidate because she is a center-right woman with a leftist alliance,” she explains.

Sandra says there was a greater articulation of feminists to push women’s candidacies in this last election, but that most, including hers, have not gone beyond the party’s internal lists.

“We formed a group to boost women’s applications, which also fueled my campaign. But these candidacies had to be negotiated because we do not have a party and in this negotiation, in some cases the women were in second place, and I was not chosen for re-election,” she said.

Despite the difficulties, she also comments that feminists are beginning to think of other strategies to elect more women.

“This is not the first time of this group, but this time it seems to be much more inclusive and allows us to discuss what it means for the upcoming elections, whether we try to form an alliance with a political party or make a party of our own, which is not just one women’s party, but one where we have a key role in the party. We have come from the experience of turning our backs on the electoral political participation until the moment we are in now, to build a party of our own,” she argues.

Of the 158 seats in the Congress of the Republic of Guatemala, 132 are occupied by men. Currently, Sandra is one of the 26 MPs in the parliament, that is, she is part of the 16% of women in the House, a percentage close to that of Brazil, which rose from 10 to 15% in the last elections.

In Guatemala, there is no law that establishes minimum quotas for the participation of women in political parties.

Lesbian visibility

If egalitarian feminine representation is still a distant perspective of the powers in Guatemala, the picture becomes even more complicated for women like Sandra Moran, an openly lesbian and popular leader.

Also, if in 2015 Sandra became recognized as the first lesbian congresswoman in the country, the path of her political action to this point is enduring: in 1995, Sandra came out about her sexual orientation and began to participate in the organization of the first collective of lesbian women of Guatemala.

Despite this, the activist acknowledges that lesbian women are still very invisible in politics and continue in a kind of “closet” in terms of representation.

“I have always been in many meetings in different parts of the world, and I see and do not understand very well the fact that lesbian women are absent from politics. In Guatemala, lesbian women are the least organized, including those who least relate politically, a contradiction” she laments.

Speaking about the lack of representation of lesbian women, Morán also comments on the violence that the LGBT population, in general, suffers in her country. In October 2018, conservative groups presented a Bill for the Protection of Life and Family that includes, among its articles, the prohibition of marriages and civil unions for persons of the same sex.

“One of the things I said to my male and female comrades about this terrible law they want to pass in Guatemala is that what they want is for us to be invisible. And we have to be more visible,” she says.

Sandra, who ends her tenure in January 2020 and is not running for re-election, believes that one of the strategies needed to combat lesbian invisibility is for grassroots movements and organizations to take up this issue.

“We are in the movements, but the visibility and the articulation are lacking. Which does not mean that we are going to leave the movements we are in, because we do not have to move away from the fight that we are in, but, to put the visibility in the internal discussion of our organizations,” she concludes.

A version of this piece originally appeared in the Brazilian media outlet, Brasil de Fato.