Expanding Economic Justice

What is the ‘economy’? Economy is the stewardship, or care, or management of home within the boundaries of the rights that we have established, so that it is the expression of that responsibility. — Gopal Dayaneni, Movement Generation¹

For May, we’re examining how important economic justice is for the struggle for liberation — and broadening our understanding of economic justice, based on learnings from our social movement partners.

When we talk about economic justice, we often think about labor and workers’ struggles. The thought is deserved and absolutely correct, especially with International Workers Day on May 1st. Grassroots International, for our part, has supported workers’ struggles like the Frente Auténtico del Trabajo in Mexico. We continue to support groups like Domestic Workers United and La Via Campesina as part of that commitment to workers and peasants.

But economic justice is more than that. As Gopal Dayaneni from our ally Movement Generation has said, even “the economy” doesn’t mean what we think it means. “Eco” is derived from the Greek word oikos, meaning home. At its essence, then, economics has to do with the management of the home. Economic justice, therefore, is about how we take care of our individual and collective homes, and each other.

With movements’ leadership, that definition puts Black, Indigenous, and feminist economies front and center. That definition intersects with climate justice through the concepts of “just transition” and of food sovereignty. It takes on questions of debt and colonialism. And lastly, it calls us to take action — to make that care real.

BLACK, INDIGENOUS, AND FEMINIST ECONOMIES

There’s a common stereotype that “workers” are white men in hardhats. That to talk of the working class is to ignore issues of race, gender, and sexuality.

That was never true, and certainly not today. From the fields of Southern plantations to under-the-table and undocumented domestic work, capitalism has always controlled Black and immigrant labor — especially women’s — through racial power structures. This is especially evident in the U.S., which has grown even more reliant on a diverse working class to make profit.

The proportion of Black, Latinx, and Asian workers in major U.S. industries has grown — going from 15-16 percent of workers in production, transportation, and material moving occupations in 1981 to 40 percent of workers in these industries in 2010.² Likewise, as globalization has driven the poor of Haiti, Bangladesh, and elsewhere into sweatshops, they too have joined a diverse and growing global working class. Today, 75 percent of garment workers worldwide are women.

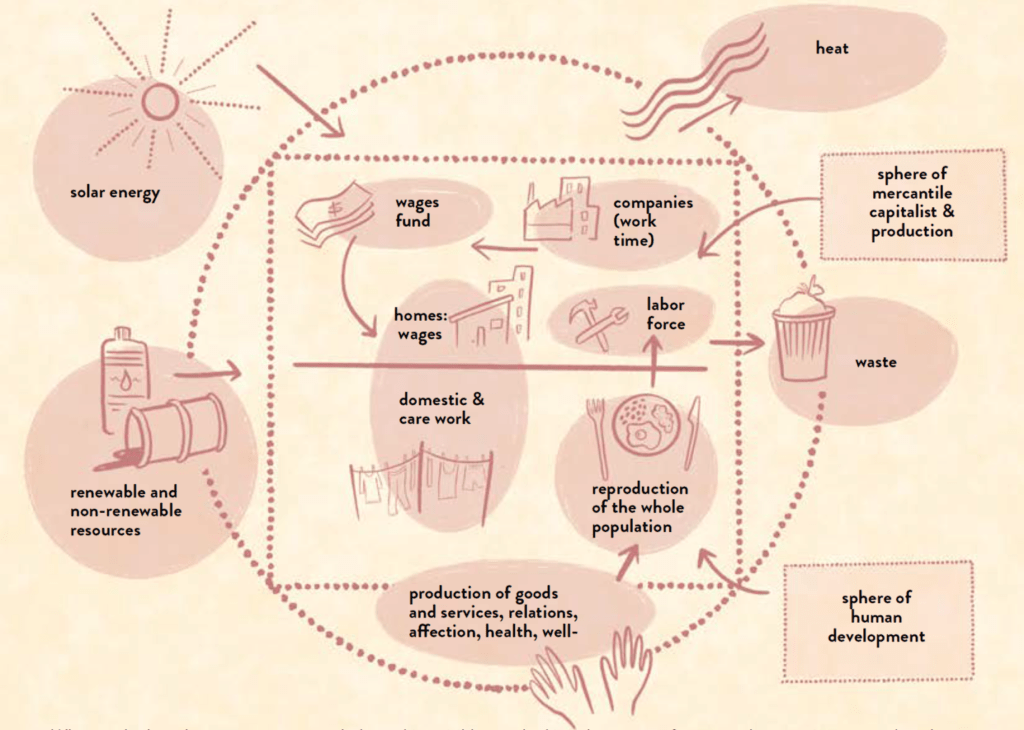

In response, many are rediscovering, recovering, and developing visions of a different economy. The Berta Cáceres International Feminist Organizing School (IFOS), for example, has sought to re-center reproduction alongside production as part of developing feminist economies for life. Grassroots has been privileged to accompany this process together with our allies, with leadership from Grassroots Global Justice Alliance, World March of Women, and the Indigenous Environmental Network. And we have been privileged to support the involvement of a number of our partners, and to learn from them along the way.

IFOS AND MAKING INVISIBLE LABOR VISIBLE

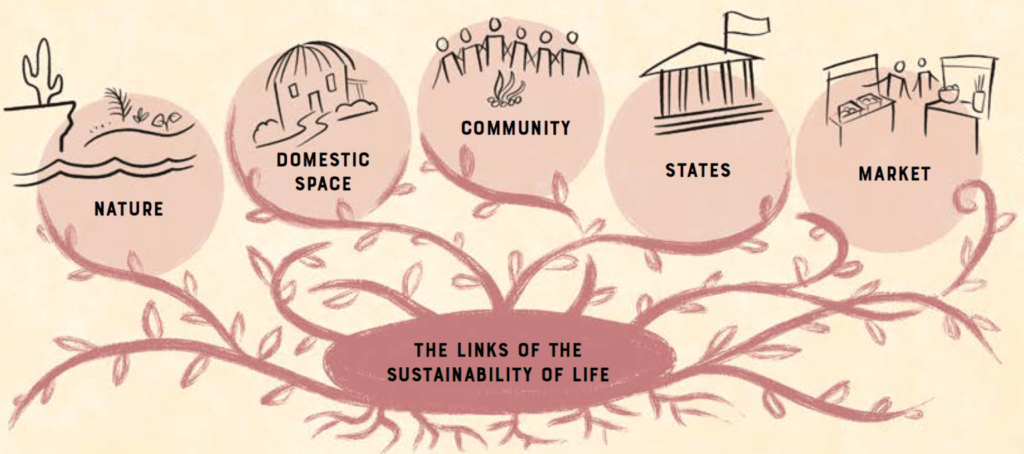

The invisible labor of women, trans, and gender non-conforming people caring for children and others in the home can be valued globally at $10.9 trillion (if this labor was paid at the rate of each nation’s minimum wage). By re-centering the labor of care, the members of IFOS charted out an alternative economy starting with the “links of the sustainability of life”:

Nature, domestic space, community, state, and the market are set into conflict with one another under capitalism. But re-centering care and the relationship between production and reproduction allows us to imagine an alternative: one based on interdependence and the sustainability of life, not competition and conflict.

INDIGENOUS PRINCIPLES OF JUST TRANSITION

Similarly, putting Indigenous and Black people — particularly women, trans, and gender non-conforming people — back into the narrative of “economy” can reshape the alternatives. We can identify locales of resistance. We can also connect future alternatives to ancestral ways of organizing collective work.

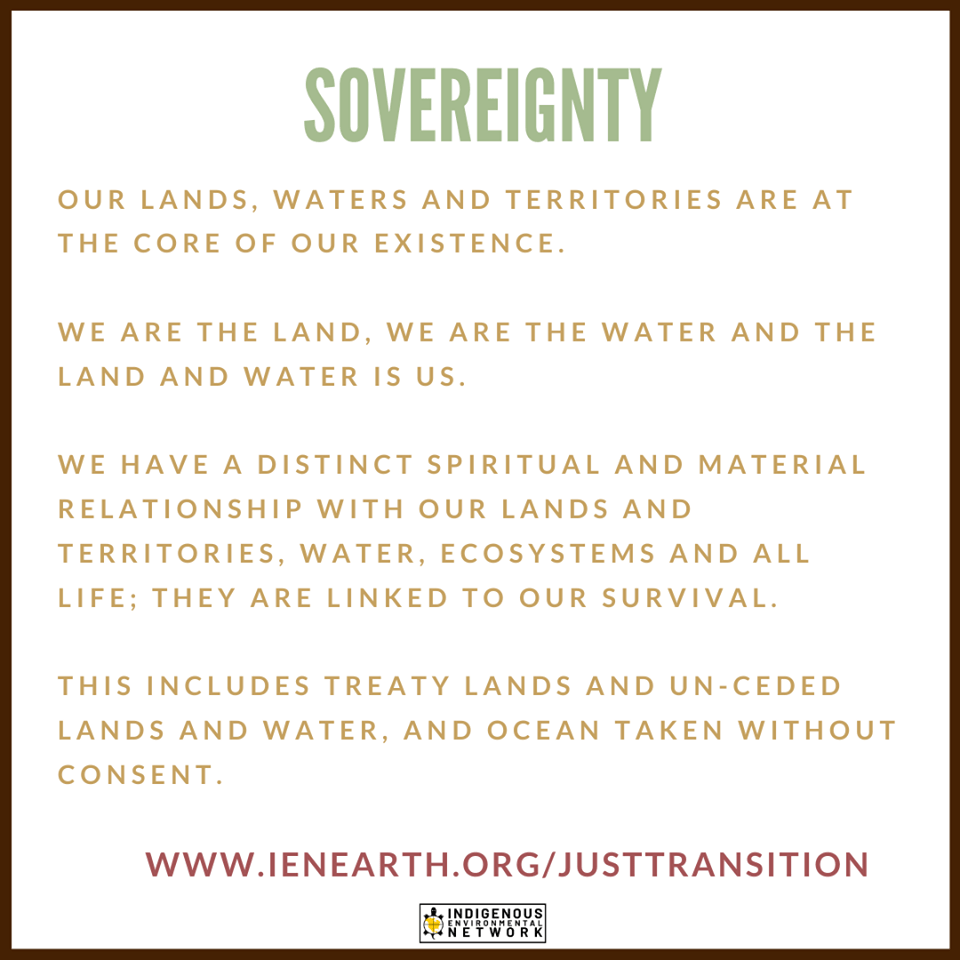

Our ally the Indigenous Environmental Network, for example, has offered Indigenous Principles of Just Transition to connect planetary stewardship, Indigenous sovereignty and economic justice. They are expanding on the framework for a future economy and incorporating long-standing Indigenous values and traditions:

“Just Transition strategies were first forged by labor unions and environmental justice groups who saw the need to phase out the industries that were harming workers, community health and the planet, while also providing just pathways for workers into new livelihoods…

In Indigenous thought, it is a healing process of understanding historical trauma, internalized oppression, and de-colonization leading to planting the seed and feeding and nurturing the Good Way of thinking.”

As the IEN and other climate justice movements make clear, if economics means the management of the home, we have to talk about the home we all share: our planet.

DEBT AND COLONIALISM

Meanwhile, our partner la Colectiva Feminista en Construcción (la Cole) is challenging the very notion of Puerto Rico’s (and the Global South’s more generally) sovereign debts.

Debt is rooted in colonization and control, especially of Black, Indigenous, and female bodies. As they say in their piece in the recently published Quién le Debe a Quién? Ensayos Transnacionales de Desobediencia Financiera (Who Owes Whom? Transnational Essays on Financial Disobedience):

Colonialism as a political project uses race as a tool for generating inequality, marking the bodies/peoples fit for capture, exploitation, rape, forced labor, extraction, impoverishment and death; namely, the bodies/peoples enabled for their dehumanization…[D]ebt is the mechanism through which the colonial system perpetuates. Debt marks bodies/peoples by banishing them, impoverishing them, extracting from them and robbing them of the possibility of a future.

This debt still keeps Puerto Rico, and especially Black women and trans Puerto Ricans, in chains. That’s why la Cole carries forward the slogan Nosotras contra la deuda (“We [women] against the debt”).

A CALL TO ACTION

Economic justice goes beyond just wage and workplace struggles, though those are essential. It requires us to rethink the narrow notion of the “economy” fed to us by mainstream media and textbooks. It calls on us to envision a different kind of world.

It also challenges us to take action. Grassroots International remains committed to our own economic redistribution — to provide resources from the Global North to frontlines of economic justice struggles worldwide. We hope you join us.

[1] https://geo.coop/articles/crisis-jurisdiction-economy [2] On New Terrain, Kim Moody, 35.