Issues we work on

Food Sovereignty

From field to plate, our food system is steeped in injustice. But social movements are working to change this in inspiring ways. Collectively, they are advancing food sovereignty, which they define as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”

Impact Overview

Our partners celebrated the milestone of 25 years of the global struggle for food sovereignty in 2021, and we are honored to have accompanied them along the way. Over the years, food sovereignty movements have generated extensive public debate over free trade, industrial agriculture, genetically modified crops, and other corporate-driven and top-down approaches.

Simultaneously, movements have built inspiring alternatives such as thriving territorial markets based on agroecological production by peasants, fishers, and other small-scale food providers. They have demonstrated the ability of such alternatives to be scaled both upward and outward, with society-wide benefits. Food sovereignty is increasingly making its way into policy spaces, with numerous examples of food sovereignty legislation from the local to global levels. In the process, it is reshaping global debates around food and agriculture.

Work we’re accompanying:

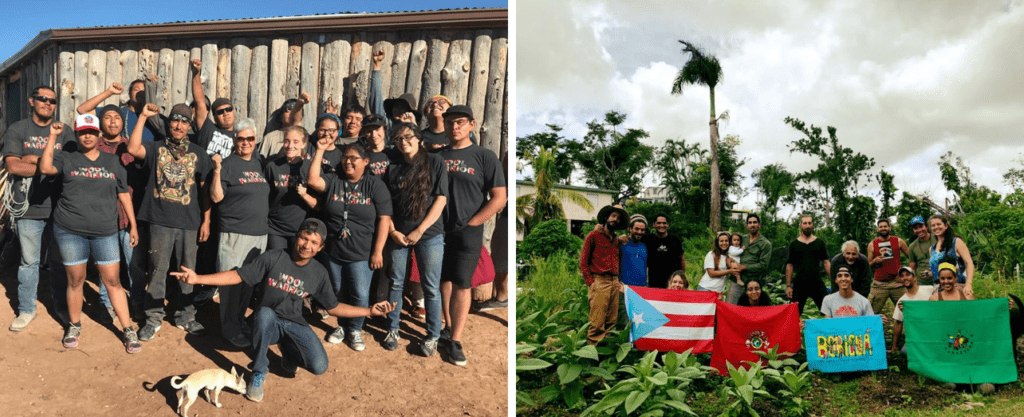

- A global process of convergence among diverse movements from across the world to develop a common framework and action agenda for food sovereignty

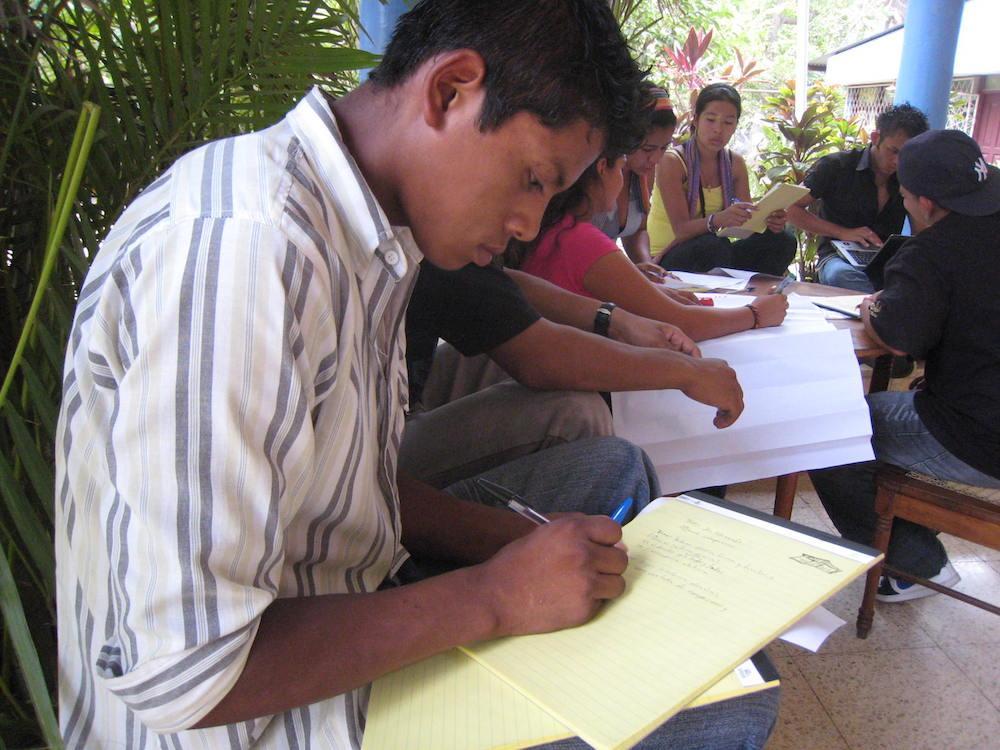

- A growing network of peasant-run schools providing political and technical training on agroecology – a key pillar of food sovereignty that involves farming in sync with nature

- The strengthening of community-controlled seed banks and other forms of resistance to the corporate takeover of seeds

- Organizing and advocacy within the US to change national food and agriculture policies that have global implications

- Engagement of social movements in policy spaces across multiple scales to wrest control over the food system from corporations and back to communities

Despite there being more than enough food for every person on the planet, hunger continues to rise.

In 2020, 3.1 billion people could not afford a healthy diet 1. And paradoxically, the majority of the world’s hungry are food providers themselves, and their families.

The extreme contradictions inherent in our food system are what gave rise to the food sovereignty movement more than 25 years ago. In 1996, as world leaders gathered in Rome for the World Food Summit, they failed to invite key actors: movements of small-scale food providers who were producing the majority of the world’s food while bearing the brunt of unjust agricultural policies. Undeterred, they showed up in Rome anyway, under the banner of our global movement partner, La Via Campesina. Taking to the streets, they asserted that there could be no food security without food sovereignty, or the right of the people to control their own food systems.

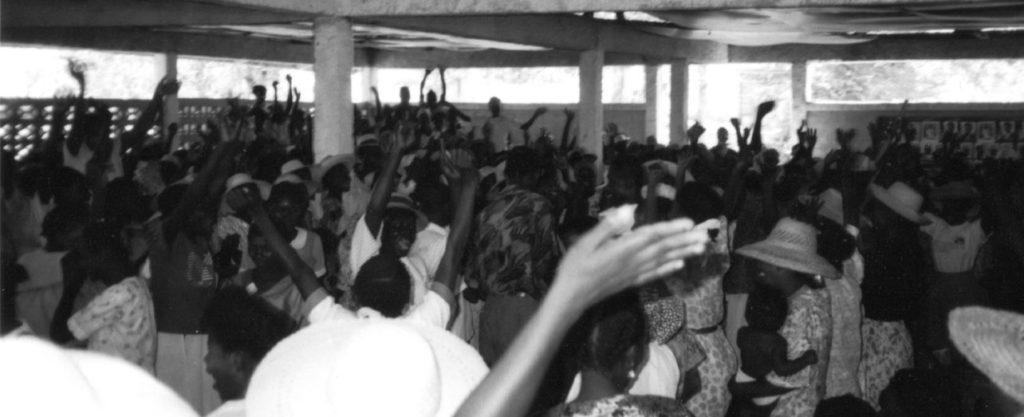

In the years since, food sovereignty has grown in visibility, power and impact. A key moment was the Nyéléni Global Forum for Food Sovereignty held in Mali in 2007. There, an assemblage of movements even more diverse than a decade earlier, including urban, consumer, labor, agrarian, and environmental justice movements, articulated both a common definition (shared above) and framework for food sovereignty, including the following six pillars:

- focuses on food for people

- values food providers

- localizes food systems

- puts control locally

- builds knowledge and skills

- works with nature

This collective articulation has helped to unite movements in struggle across the globe, in all of their diversity, toward a shared vision of transformation. A key part of that work has been the articulation of agroecology, bridging the worlds of food sovereignty and climate justice. Today, our movement partners are in the midst of a new and even more extensive Nyéléni process that we are honored to support.

1 The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022 (FAO et al. 2022)